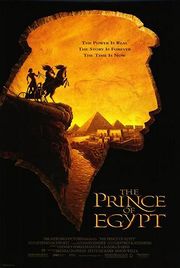

The Prince of Egypt

| The Prince of Egypt | |

|---|---|

Original poster |

|

| Directed by | Simon Wells Brenda Chapman Steve Hickner |

| Produced by | Penney Finkelman Cox Sandra Rabins Jeffrey Katzenberg (executive producer) |

| Written by | Philip LaZebnik Nicholas Meyer |

| Starring | Val Kilmer Ralph Fiennes Michelle Pfeiffer Sandra Bullock Jeff Goldblum Patrick Stewart Danny Glover Steve Martin Martin Short |

| Music by | Stephen Schwartz (songs) Hans Zimmer (score) |

| Editing by | Nick Fletcher |

| Studio | DreamWorks Animation |

| Distributed by | DreamWorks Pictures |

| Release date(s) | December 18, 1998 |

| Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English, Hebrew |

| Budget | $70 million[1] |

| Gross revenue | $218,613,188[1] |

| Followed by | Joseph: King of Dreams (2000) |

The Prince of Egypt is a 1998 American animated film, the first traditionally animated film produced and released by DreamWorks Animation. The story follows the life of Moses from his birth, through his childhood as a prince of Egypt, and finally to his ultimate destiny to lead the Hebrew slaves out of Egypt, which is based on the Biblical story of Exodus. The film was directed by Brenda Chapman, Simon Wells and Steve Hickner. The film featured songs written by Stephen Schwartz and a score composed by Hans Zimmer. The voice cast featured a number of major Hollywood actors in the speaking roles, while professional singers replaced them for the songs. The exceptions were Michelle Pfeiffer, Ralph Fiennes, Ofra Haza, Steve Martin, and Martin Short, who sang their own parts.

The film was nominated for best Original Music Score and won for Best Original Song at the 1999 Academy Awards for "When You Believe".[2] The pop version of the song was performed at the ceremony by Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey. The song, co-written by Stephen Schwartz, Hans Zimmer and with additional production by Babyface, was nominated for Best Original Song (in a Motion Picture) at the 1999 Golden Globes,[3] and was also nominated for Outstanding Performance of a Song for a Feature Film at the ALMA Awards.

The film was released in theaters on December 18, 1998, and on VHS and DVD on September 14, 1999. The film went on to gross $218,613,188 worldwide in theaters[1], making it the second traditionally animated feature not released by Disney to gross over $100 million in the U.S. (after The Rugrats Movie), Prince of Egypt became the top grossing non-Disney animated film until 2000 when it was out-grossed by the stop motion film Chicken Run. The film also remained the highest grossing non-Disney traditionally animated film until 2007, when it was out-grossed by The Simpsons Movie.[4]

Contents |

Plot synopsis

The first song ("Deliver Us") shows Hebrew slaves labor away while Jochebed (also spelled Yocheved) (Ofra Haza), sees her fellow mothers' baby sons being taken away from them, as Pharaoh Seti I (Patrick Stewart) has ordered. Jochebed thus places her own son in a basket and sets it afloat on the Nile to be preserved by fate, singing her final lullaby ("River Lullaby", a recurring motif in the film) to the baby. Her daughter, Miriam, follows the basket and witnesses her baby brother being taken in by the Queen of Egypt (Helen Mirren) and named Moses.

The story cuts to 20 years later (according to the Bible), to show a grown Moses (Val Kilmer) and his foster-brother, Rameses II (Ralph Fiennes), racing their chariots through the Egyptian temples, destroying many idols of the gods (and the nose of the still-under construction Sphinx). When they are lectured by their father, Seti I, later on for their misdeeds, Rameses is offended that his father believes he would bring down the Dynasty. Moses later remarks that Rameses wants the approval of his father, but lacks the opportunity. Moses goes to cheer his brother up, making joking predictions ("Statues cracking and toppling over, the Nile drying up; single handedly you will manage to bring the greatest kingdom on Earth to ruins!"). They then stumble in late to a banquet given by Seti, discovering that he has named Rameses as Prince Regent and given him authority over all of Egypt's temples. In thanks, Rameses appoints Moses as Royal Chief Architect. As a tribute to Rameses, the high priests Hotep (Steve Martin) and Huy (Martin Short) offer Tzipporah (Michelle Pfeiffer), a Midian girl they kidnapped as a concubine for him. Rameses rejects the offer and gives Moses the girl, who insults both of them and is pushed into a fountain by Moses in response. She eventually escapes, with Moses' help. Moses is led to a small spot in Goshen where he is reunited with Miriam (Sandra Bullock) and Aaron (Jeff Goldblum), his siblings. There, Miriam tells him the truth about his past. Moses at first is in denial ("All I Ever Wanted"), but a nightmare and talks with his adoptive parents help him realize the truth. Moses eventually kills an Egyptian guard by accident, who was abusing an old slave, and runs away in exile.

Moses is dragged to Midian by holding onto a bag of water being carried by a camel. There, he saves Tzipporah's sisters from bandits. He is welcomed warmly by Tzipporah's father, Jethro (Danny Glover) the High Priest of Midian and his people. Moses becomes a shepherd and gradually earns Tzipporah's respect and love, culminating in their marriage ("Through Heaven's Eyes"). Moses soon comes into contact with the burning bush while chasing a stray lamb and is instructed by God (voiced by Val Kilmer) to free the slaves from Egypt. God then empowers Moses' shepherding staff with the ability to do great wonders, the greatest being to shepherd his people to freedom. Tzipporah returns with him to find the slaves in even worse condition than before. He discovers that Rameses is now Pharaoh and has a wife and a young son. Moses tells Rameses to let his people go, demonstrating the power behind him by changing his shepherding staff into a snake. Hotep and Huy boastfully repeat this transformation ("Playing with the Big Boys Now"), conujuring many of Egypt's Gods in the process; behind their backs, the snake created by Moses eats both of their snakes. Rather than being persuaded, Rameses is hardened and orders the slaves' work to be doubled.

Out in the work field, Moses is struck down by an elder Hebrew into a muddy pit, and then is confronted by Aaron, who blames him for the excess workload. Moses, with Miriam's help, tells the Hebrews to believe that freedom will come. He confronts Rameses, who is passing on his boat in the Nile. Rameses orders his guards to bring Moses to him, but they turn back when Moses turns the river into blood. During the nine of the Plagues of Egypt occur ("The Plagues") Moses feels tortured inside, betraying Rameses and leaving Egypt in ruins. Moses soon returns to Rameses to warn him about the final plague. After an almost-tender moment between the brothers, Moses is told never to come to Rameses again, even though Moses warns Rameses that an even worse plague is about to transpire, and to think of Rameses' only son. Moses then instructs the Hebrews to paint lamb's blood above their doors for the coming night of Passover. God comes through during the night, killing all the firstborn children of Egypt, including Rameses' son. Moses once more visits the grief-stricken Rameses, who is cradling the body of his own son. Rameses reluctantly lets the Hebrews go. Moses leaves and breaks down in tears outside, his spirit broken after causing his brother so much pain.

The next morning, the Hebrews happily pack, leave their enslavement, and eventually find their way to the Red Sea ("When You Believe"), but turn around to find out Rameses has changed his mind and is pursuing them with his army. Moses parts the Red Sea, while behind him a pillar of fire writhes before the Egyptians, blocking their way. The Hebrews cross on the sea bottom; when the army gives chase, the water closes over the Egyptians, and the Hebrews are freed. Rameses, who has been hurled back to the shore by the collapsing waves, is left yelling his brother's name in defeated fury. Moses turns from the shore and begins to lead his people onward; only briefly looking back towards the sea in Rameses' direction, murmuring sadly; "Good bye, Brother". The last scene of the film shows Moses delivering the Ten Commandments to his people as Jochebed's voice echoes in the background.

Cast

- Val Kilmer as Moses, the protagonist of the film. He is actually a Hebrew who was adopted by Pharaoh Seti, but eventually runs away after being clued in to his true heritage. Kilmer also plays God, who serves as Moses's guide throughout his quest to free the Hebrew slaves.

- Ralph Fiennes as Ramses II, Moses's foster brother and eventual successor to his father, Seti. When Moses returns to Egypt, Rameses is Pharaoh; at that point, Rameses becomes the main antagonist of the film. He constantly refuses to free the Hebrew slaves, thereby incurring the plagues upon Egypt.

- Michelle Pfeiffer as Zipporah

- Sandra Bullock as Miriam

- Jeff Goldblum as Aaron

- Patrick Stewart as Pharaoh Seti I

- Danny Glover as Jethro

- Helen Mirren as Queen Tuya

- Steve Martin as Hotep

- Martin Short as Huy

- Ofra Haza as Yocheved

- Amick Byram as Moses (singing voice)

- Sally Dworsky as Miriam (singing voice)

- Eden Riegel as Young Miriam (singing voice)

- Brian Stokes Mitchell as Jethro (singing voice)

- Linda Dee Shayne as Queen Tuya (singing voice)

Director Brenda Chapman briefly voices Miriam when she sings the lullaby to Moses. The vocal had been recorded for a scratch audio track, which was intended to be replaced later by Sally Dworsky. The track turned out so well that it remained in the film.

Production

The idea for the film came about at the formation of DreamWorks, when the three partners, Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen, were meeting in Spielberg's living room.[5] Katzenberg recalls that Spielberg looked at him during the meeting and said, "You ought to do the Ten Commandments."[5]

Story development

The Prince of Egypt was "written" throughout the story process. Beginning with a starting outline, Story Supervisors Kelly Asbury and Lorna Cook led a team of 14 storyboard artists and writers as they sketched out the entire movie - sequence by sequence. Once the storyboards were approved, they were put into the Avid Media Composer digital editing system by editor Nick Fletcher to create a "story reel" or animatic. The story reel allowed the filmmakers to view and edit the entire movie in continuity before production began, and also helped the layout and animation departments understand what is happening in each sequence of the film.[6] After casting of the voice talent concluded, dialogue recording sessions began. For the film, the actors record individually in a studio under guidance by one of the three directors. The voice tracks were to become the primary aspect as to which the animators built their performances.[6] Because DreamWorks was concerned about historical and theological accuracy, Jeffrey Katzenberg decided to call in Bible scholars, Christian, Jewish and Muslim theologians, and Arab American leaders to help his movie be more accurate and faithful to the original story. After previewing the developing film, all these leaders noted that the studio executives listened and responded to their ideas, and praised the studio for reaching out for comment from outside sources.[5]

Art and visual design

Art directors Kathy Altieri and Richard Chavez and Production Designer Darek Gogol led a team of nine visual development artists in setting a visual style for the movie that was representative of the time, the scale and the architectural style of Ancient Egypt.[6] Part of the process also included the research and collection of artwork from various artists, as well as taking part in trips such as a two-week travel across Egypt by the filmmakers before the production of the film began.[6]

There are 1192 scenes in film, and 1180 of them have special effects in them. These special effects were elements such as wind blowing or environmental things such as dust or rainwater. There were also effects design in terms of lighting, as it casts its shadows and images into a given scene. In the end, these effects helped the animators graphically illustrate scenes such as the 10 plagues and the parting of the Red Sea.[5]

Character and background design

Character Designers Carter Goodrich, Carlos Grangel and Nicolas Marlet worked on setting the design and overall look of the characters. Drawing on various inspirations for the widely known characters, the team of character designers worked on designs that had a more realistic feel than the usual animated characters up to that time.[6] Both character design and art direction worked to set a definite distinction between the symmetrical, more angular look of the Egyptians versus the more organic, natural look of the Hebrews and their related environments.[6] The Backgrounds department, headed by supervisors Paul Lasaine and Ron Lukas, oversaw a team of artists who were responsible for painting the sets/backdrops from the layouts. Within the film, approximately 934 hand-painted backgrounds were created.[6]

Music and sound

The task of creating the voice of God was given to Lon Bender and the team working with the film's music composer, Hans Zimmer.[7] "The challenge with that voice was to try to evolve it into something that had not been heard before," says Bender. "We did a lot of research into the voices that had been used for past Hollywood movies as well as for radio shows, and we were trying to create something that had never been previously heard not only from a casting standpoint but from a voice manipulation standpoint as well. The solution was to use the voice of actor Val Kilmer to suggest the kind of voice we hear inside our own heads in our everyday lives, as opposed to the larger than life tones with which God has been endowed in prior cinematic incarnations."[7]

Composer and lyricist Stephen Schwartz began working on writing songs for the film from the very beginning of the film's production. As the story evolved, he continued to write songs that would serve to both entertain and help move the story along. Composer Hans Zimmer arranged and produced the songs and then eventually wrote the score for the film. The film's score was recorded entirely in London, England.[6]

Soundtrack

Four soundtracks were released simultaneously for The Prince of Egypt, each of them aimed towards a different target audience. While the other two accompanying records, the country-themed "Nashville" soundtrack and the gospel-based "Inspirational" soundtrack, functioned as movie tributes, the official Prince of Egypt soundtrack contained the actual songs from the film.[8] This album combines elements from the score composed by Hans Zimmer, and movie songs by Stephen Schwartz.[8] The songs were either voiced over by professional singers (such as Salisbury Cathedral Choir), or sung by the movie's voice actors, such as Michelle Pfeiffer and Ofra Haza. Various tracks by contemporary artists such as K-Ci & Jo-Jo and Boyz II Men were added, including the Mariah Carey and Whitney Houston duet "When You Believe", a Babyface rewrite of the original Schwartz composition, sung by Michelle Pfeiffer and Sally Dworsky in the movie. Amy Grant also sings a version of "River Lullaby". Also, a rare complete score was released for promotional purposes.

Ofra Haza, who voiced Yocheved, sang the opening song "Deliver Us" in 28 languages in which the film was released, in addition to her native Hebrew language.

Reception

Box Office performance

The film was a box-office success, gaining $218,613,188 worldwide[1], which easily covered its production budget of $70 million[1].

| Source | Gross (USD) | % Total | All Time Rank (Unadjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | $101,413,188[1] | 46.4% | 398[1] |

| Foreign | $117,200,000[1] | 53.6% | N/A |

| Worldwide | $218,613,188[1] | 100.0% | 319[1] |

Reviews

The Prince of Egypt received generally positive reviews from critics and at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 80 reviews collected, the film has an overall approval rating of 79%, with a weighted average score of 7/10.[9] Among Rotten Tomatoes's Cream of the Crop, which consists of popular and notable critics from the top newspapers, websites, television and radio programs,[10] the film holds an overall approval rating of 75 percent.[11] By comparison, Metacritic, which assigns a normalized 0–100 rating to reviews from mainstream critics, calculated an average score of 64 from the 26 reviews it collected.[12]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times praised the film in his review saying, "The Prince of Egypt is one of the best-looking animated films ever made. It employs computer-generated animation as an aid to traditional techniques, rather than as a substitute for them, and we sense the touch of human artists in the vision behind the Egyptian monuments, the lonely desert vistas, the thrill of the chariot race, the personalities of the characters. This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children's entertainment."[13] Richard Corliss of Time Magazine gave a negative review of the film saying, "The film lacks creative exuberance, any side pockets of joy."[14] Stephen Hunter from Washington Post praised the film saying, "The movie's proudest accomplishment is that it revises our version of Moses toward something more immediate and believable, more humanly knowable."[15] Lisa Alspector from Chicago Reader praised the film and wrote, "The blend of animation techniques somehow demonstrates mastery modestly, while the special effects are nothing short of magnificent."[16] Houston Chronicle's Jeff Millar reviewed by saying, "The handsomely animated Prince of Egypt is an amalgam of Hollywood biblical epic, Broadway supermusical and nice Sunday school lesson."[17] James Berardinelli from Reelviews highly praised the film saying, "The animation in The Prince of Egypt is truly top-notch, and is easily a match for anything Disney has turned out in the last decade", and also wrote "this impressive achievement uncovers yet another chink in Disney's once-impregnable animation armor."[18] Liam Lacey of Globe and Mail gave a somewhat negative review and wrote, "Prince of Egypt is spectacular but takes itself too seriously."[19] The Nostalgia Critic placed the film as #8 on his list of the Top 11 Underrated Nostalgia Classics, placing it low on the list because it was a box office success, but has not been talked about since.[20]

Awards and nominations

- Academy Awards[2]

- Academy Award for Best Original Music Score (Nominated)

- Academy Award for Best Original Song for "When You Believe" (Won)

- Golden Globe Awards[3]

- Best Original Score (Nominated)

- Best Original Song for "When You Believe" (Nominated)

- Annie Awards[21]

- Best Animated Feature (Nominated)

- Individual Achievement in Directing to Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner, and Simon Wells (Nominated)

- Individual Achievement in Storyboarding to Lorna Cook (Story supervisor) (Nominated)

- Individual Achievement in Effects Animation to Jamie Lloyd (Effects Lead - Burning Bush/Angel of Death) (Nominated)

- Individual Achievement in Voice Acting to Ralph Fiennes ("Rameses") (Nominated)

Differences from the Biblical story

Although based on the Biblical story of Exodus, the film takes considerable liberties with the Biblical story. It opens with a textual disclaimer stating that, "artistic license has been taken." Some differences are listed below:

- In the Bible, Pharaoh's daughter finds Moses in the Nile and sends her handmaids to retrieve him. In the movie, Pharaoh's wife found him, and retrieves the basket herself.[22](Ex.2: 9)

- In the Bible, Moses' sister comes to Pharaoh's daughter and offers her a woman (Moses' real mother) who can nurse Moses; this is not shown in the film.[22]

- In the New Testament, in the Book of 2nd Timothy, Paul lists the names of the magicians of Pharaoh as Jannes and Jambres (according to Hebrew tradition.) In the film, their names are Hotep and Huy.

- In the Bible, Moses kills an Egyptian guard and buries his body, whereas in the film Moses flees after accidentally knocking the guard off the large scaffolding.[22](Ex. 2:11-12)

- In the Bible, Moses was roughly eighty by the time he returned to Egypt, and had two sons. In the film, he appears fairly young, and his sons are not depicted.[22]

- In the film, Moses turned his staff into a snake when he first saw Pharaoh. In the Bible, Aaron performed it during his second encounter.

- In the Bible, Moses is "slow of tongue", and Aaron speaks for him. In this film, as is often the case with dramatic adaptations of this passage, Moses alone speaks for God to Pharaoh.

- In the Bible, the pharaoh tried to kill Moses, but in the film Rameses did not.

- Current hypotheses on the Exodus timeline have Tuthmose III or Ramses as the Pharaoh of Oppression. (However, it must be noted that there is no historical data to support these hypotheses.) In the film, it is Seti, with Ramses being his successor. This assumption was also present in an earlier Exodus film, The Ten Commandments.

Controversy

The Maldives was the first of two Muslim countries to ban the film. The country's Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs stated, "all prophets and messengers of God are revered in Islam, and therefore cannot be portrayed".[23][24] Following this ruling, the censor board banned the film in January 1999. In the same month, the Film Censorship Board in Malaysia banned the film, but did not provide a specific explanation. The board's secretary said that the censor body ruled the film was "insensitive for religious and moral reasons".[25] However, the film is now openly available on DVD in retail stores in both countries.

The film was banned in Egypt,[26] a predominantly Muslim country, as the depiction of Islamic prophets is forbidden in Islam. There was also discontent concerning the reference to Rameses (or Ramses in Egypt) as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Rameses II is highly regarded in Egypt, and is widely believed by the people to have been deceased prior to the events of the Hebrew enslavement and Exodus.

See also

- Joseph: King of Dreams, a direct-to-video prequel also made by DreamWorks.

- The Ten Commandments

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Prince of Egypt (1998)". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=princeofegypt.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Academy Awards, USA: 1998". awardsdatabase.oscars.org. http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org/ampas_awards/DisplayMain.jsp?curTime=1235853348172. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "HFPA-Awards search". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. http://www.goldenglobes.org/browse/year/1998. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "Highest grossing animated films". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/genres/chart/?id=animation.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Dan Wooding's strategic times". Assistnews.net. http://www.assistnews.net/strategic/s0000023.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 "Prince of Egypt-About the Production". Filmscouts.com. http://www.filmscouts.com/SCRIPTs/matinee.cfm?Film=pri-egy&File=productn. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Sound design of Prince of Egypt". Filmsound.org. http://www.filmsound.org/studiosound/postpro.html. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "SoundtrackNet:The Prince of Egypt Soundtrack". SoundtrackNet.net. http://www.soundtrack.net/albums/database/?id=1648. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt movie reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/prince_of_egypt/?name_order=asc. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "Rotten Tomatoes FAQ: What is Cream of the Crop". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/pages/faq#creamofthecrop. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt: Rotten Tomatoes' Cream of the Crop". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/prince_of_egypt/?critic=creamcrop. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt (1998): Reviews". Metacritic. CNET Networks. http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/princeofegypt?q=prince%20of%20egypt. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt: Roger Ebert". Chicago Suntimes. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19981218/REVIEWS/812180303/1023. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "Can a Prince be a movie king? - TIME". Time Magazine. 1998-12-14. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989841-1,00.html. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt: Review". Washington Post. 1999-09-07. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/princeofegypthunter.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt: Review". Chicago Reader. http://onfilm.chicagoreader.com/movies/capsules/17161_PRINCE_OF_EGYPT. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The Prince of Egypt: Movie Reviews". Houston Chronicle. http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/ae/movies/reviews/161442.html. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "Review:The Prince of Egypt". Reelviews.net. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/p/prince_egypt.html. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The Globe and Mail Review:The Prince of Egypt". The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/ArticleNews/movie/MOVIEREVIEWS/19981218/TALAIM. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Top 11 Underrated Nostalgic Classics

- ↑ "Legacy: 22nd Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (1999)". Annie Awards. http://annieawards.org/27thwinners.html. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 The Prince of Egypt, Let Us Reason

- ↑ "There can be miracles", The Independent, January 24, 1999

- ↑ "CNN Showbuzz - January 27, 1999". CNN. 1999-01-27. http://www.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/News/9901/27/showbuzz/index.html. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ "Malaysia bans Spielberg's Prince". BBC News. 1999-01-27. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/263905.stm. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ "Titles banned in Egypt". IMDB. http://us.imdb.com/List?certificates=Egypt:(Banned)&&heading=14;Egypt:(Banned). Retrieved 2009-02-28.

External links

- The Prince of Egypt at the Big Cartoon DataBase

- The Prince of Egypt at the Internet Movie Database

- Joseph: King of Dreams at the Internet Movie Database (prequel to The Prince of Egypt)

- The Prince of Egypt at Allmovie

- Joseph: King of Dreams at Allmovie (prequel to The Prince of Egypt)

- The Prince of Egypt at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Prince of Egypt at Box Office Mojo

- A comparison of 'The Prince of Egypt' with 'The Ten Commandments' movie, the biblical story and the Jewish Midrash

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Titanic |

Academy Award for Best Original Song 1998 |

Succeeded by Tarzan |

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||